What do we know about working equid populations?

Horses, donkeys and mules are often excluded from livestock censuses, but population data is key for improving their health and welfare. A new study uncovers the critical gaps and recommends improvements.

By Fiona Allan

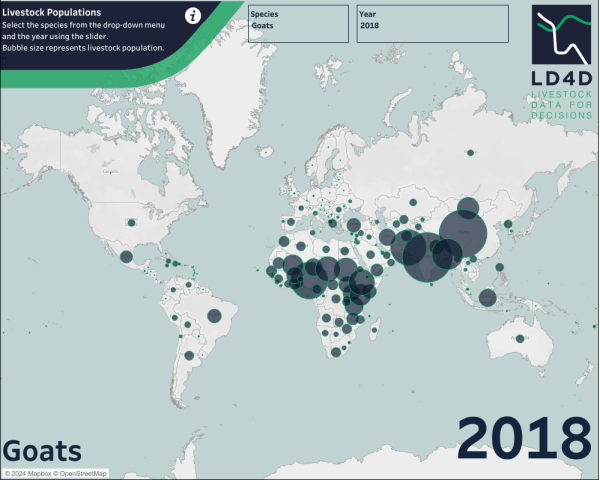

Globally, livestock make vital contributions to the livelihoods of families and communities, and especially so in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Whilst production animals provide nutrition, income and security, working animals are also sources of income from agriculture, transportation and tourism. Working equids such as horses, mules and donkeys have only been formally recognised as livestock relatively recently. These animals are often the most valuable asset a farmer owns, yet they frequently go unnoticed by governments and policy-makers. Working equids are often excluded from livestock censuses, resulting in severe data gaps about these important animals.

Keen to better establish equid population numbers, international NGO Brooke: Action for Working Horses and Donkeys partnered with SEBI-Livestock to analyse the landscape of equid data. The goal of this new study was to establish population numbers and the methods used to generate these data, as well as to investigate the problems and challenges in data collection.

The challenges for counting working equids

Our research looked at available data in 34 low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). Data collection processes were analysed for each country, revealing many challenges. The highly diverse purposes of keeping horses, donkeys and mules create challenges in implementing censuses on the ground. For example, equids which provide traction might be counted in agricultural surveys, while animals used for sport or leisure purposes would be captured in a different census. Organisations will often collect specific data to suit their requirements, and minimal, if any, data are collated for working equids. And data are frequently absent for animal populations which are perceived to generate less economic value – such as donkeys (PDF) - or for those which are less formally categorised.

An underlying problem that contributes to poor data in the livestock sector as a whole, is low capacity in many countries to undertake quantitative data analysis. There may also be a lack of analytical expertise and weak demand for quality statistical data, especially in rural settings. Despite the requirement for UN member countries to provide official statistics to the Food and Agriculture Organization, of the 34 case study countries, only 13 had conducted agricultural or livestock censuses in the previous ten years. Livestock on small-holdings (below a prescribed minimum size) are often excluded from censuses, which means that working equids are further overlooked, as they are usually kept in small numbers at the household, rather than on large farms. In many cases, data collection is not regular, and figures are often generated using extrapolation models which may not be based on recent or accurate empirical, ground-truthed data. Finally, official channels for data transfer between governments and FAO appeared lacking, with data missing and frequent broken or inactive links to databases on government websites.

New data-driven insights

The study concludes that current methods make it impossible to establish accurate equid population data. It would appear that equid populations are marginalised. In the case of working equids, where they are not properly acknowledged as livestock, they are often excluded from the agricultural context and so are excluded from enumeration.

The study highlighted an abundance of negative attitudes, towards donkeys in particular, with studies finding that LMIC governments rarely allow budgetary expenditure on health or welfare of ‘less regarded species’ like donkeys and smallholder donkey farmers reported being excluded from livestock development policies. Whilst it was not the purpose of the study, it appears that there is a lack of evidence on the economic impact that working equids make, in order to redress the negative perceptions of their low socio-economic status. Within censuses and surveys, equids are often referred to as ‘others’, with this reference not helping to raise the status of equids within the wider livestock environment.

Implications and next steps

Our analysis highlights a complex mix of problems that contribute to working equid population data gaps, including knowledge, resources, capacity, economics and socio-cultural conventions and attitudes. These problems must first be recognised in order to inform policy and action.

There is no easy solution for more accurate enumeration of equids, but the full recognition of working equids as livestock would help their inclusion. As has been said by Brooke’s ex-CEO Petra Ingram, the “challenge is to take [the UN’s recognition of working equids as livestock] to national governments, and help them adapt their livestock policies to include equine welfare.”

Countries can take an important step by clarifying and harmonising the classification of equids, and undertaking surveys that capture data on their purposes. Working equids can only be acknowledged as such if their purpose is known. Disaggregated data must be collected for each equid species, as they each have their own health and social plights. More funding for development programmes, with budgets for data components, could help break the cycle of inadequate data. Ultimately, it is improved data that will inform research and allow for a positive cycle of ‘good data’.

One promising development is the 50x2030 initiative, which aims to close agricultural data gaps by supporting 50 low and middle-income countries to produce, analyse, interpret, and apply data insights to decision-making. They have produced survey instruments that include equids as a unique category. Funders can support such initiatives to include equid data within the wider livestock sector. Official, disaggregated population data will help decision-makers accurately monitor national and global trends, while standardised data on the purposes of working equids will demonstrate how these animals contribute to supporting peoples’ livelihoods in LMICs.

More information

- Policy summary: Working Equids in Numbers: Why Data Matters for Policy

- Report: A Landscaping Analysis of Working Equid Population Numbers in LMICS, with Policy Recommendations

Fiona Allan is a consultant working with SEBI-Livestock, the Centre for Evidence Based Interventions in Livestock.

Header photo: Maasai women using donkeys to carry water. Credit: Brooke Action for Working Horses and Donkeys